“When I was a teenager I kept a picture of Daniel Day Lewis in a heart-shaped frame on my night table. These are some of the fiercest crushes I’ve lived through, and some of my worst breakups.”

My earliest writings are still some of my finest. In junior high, because I was a ham, I pandered to my friends by writing Choose Your Own Adventure stories in which they were the protagonists. These stories were written in second person, and focused on romance plots (“You are standing on a windswept moor at twilight, the sun is setting behind your amber locks, you are lit like a fiery torch...” etc.) and they were populated by characters from popular films. My chosen form was the diamond-shaped folded note, and length was constrained by the maximum width of notebook pages that when thus folded would still slide through the air vent of a locker.

The recipient chose the character/actor who currently held real estate in their heart, I drafted three or four fairly PG sexy adventures based on scenes from the movie (it was the ’90s…think Crocodile Dundee, or Tom Cruise in Cocktail), now recast as the love interest to my friend/reader, who navigated by multiple choice options. I did most of my writing during biology or algebra class (hours four and five), and then self-distributed the following day during “office”—that magic hour where I was assigned to do menial secretarial tasks for the ladies in the principal’s office. (The principal was a coach, so he was never there. Most of the teachers were also coaches, and so also often not there). Every day in zero hour, I stuffed my romantic oeuvre into the lockers of my friends, while collecting the attendance slip papers clipped to each of the classroom doors.

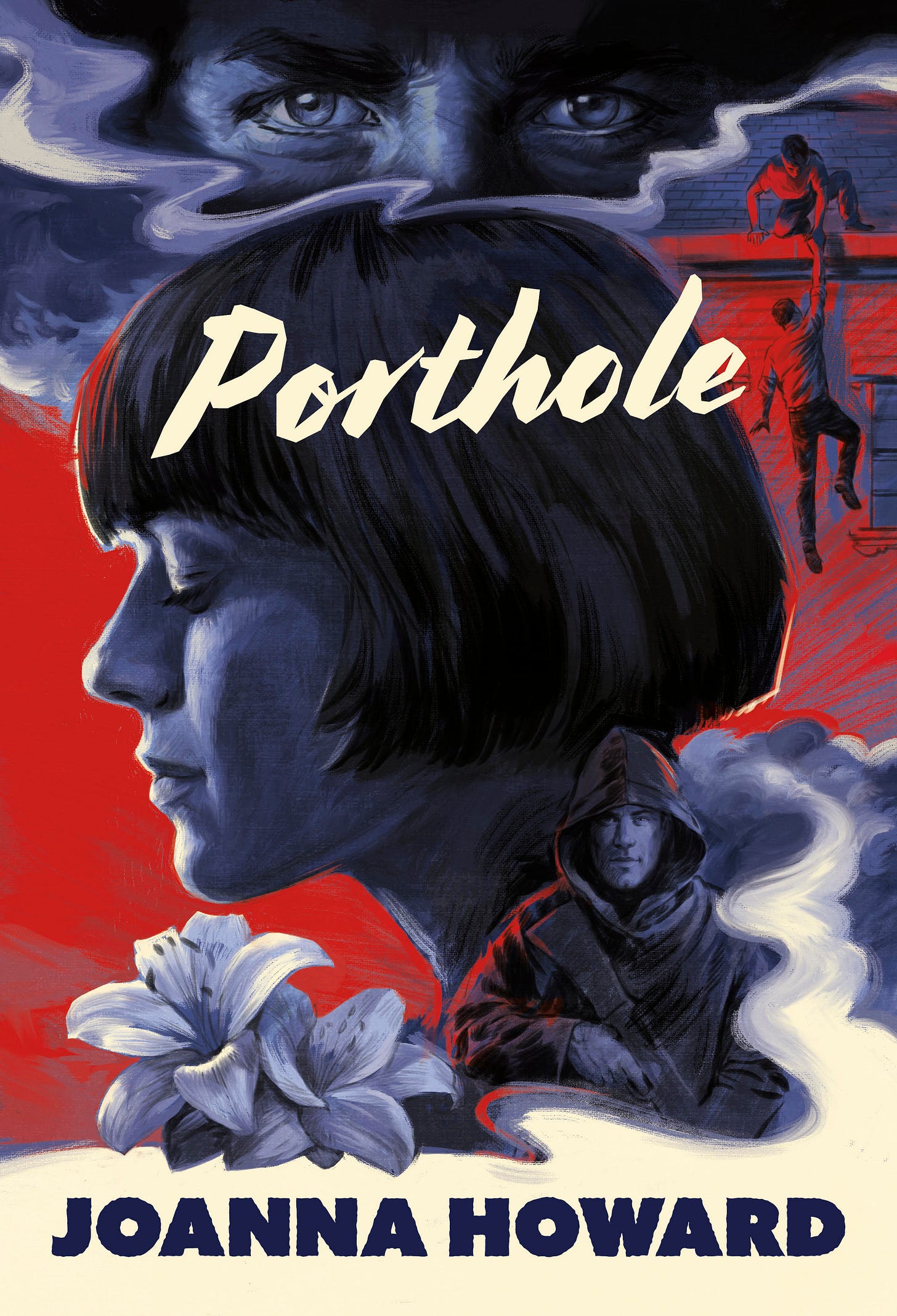

I haven’t thought about it for years, but when I was finishing up the edits on my new novel Porthole I realized that this “serious” novel I’d been laboring over for a decade was really an extension of my junior high model: collaged scenes from my favorite films, populated by mash-up versions of the actor crushes I’ve had over the years—not exactly navigated by multiple choice, but definitely focused on the fallout from the choices my character had made in her rather vexed career as a filmmaker. When I began, I thought art is art, so the protagonist could be a version of me, and I chose the first person for the point of view. (After all, I no longer have access to the locker vents of my friends.)

I had a few things wrong, however. The main character in my novel Porthole is a filmmaker, and I am not. The protagonist, Helena Désir, is a rare species: someone who has managed to have critical and commercial success, and beyond this, she is a woman who knows how to wear the pants in a male-dominated industry, even if at times that means pushing the boundaries of what’s acceptable for a woman in the public eye. What we share is a love of film. However, I am an obsessive movie fan, and someone without much discipline when it comes to binge-watching, and repeat play movie marathons. My relationship to the medium is not objective—though I tried to be studious and academic in my research for this book, the content really comes from the many film infatuations I’ve had over the years that derailed me from life, the universe, basic work tasks, etc.

The degree to which I feel for characters on-screen is beyond my control—the intensity of my obsession and/or identification with actors, or to be more specific, actors-as-characters. When I was a teenager I kept a picture of Daniel Day Lewis in a heart-shaped frame on my night table. These are some of the fiercest crushes I’ve lived through, and some of my worst breakups.

So when I began writing Porthole, I was trying to see through the screen to the other side, trying to get some objectivity on the form that has taken up a lot of my time and attention, even though I work in another medium entirely: words on a page! I wanted to inhabit the voice of someone who had the power and agency to build these deeply affecting immersive realms from the materials of our real world—professional actors, constructed sets, costumes—but on her side of the camera, she would control the fantasia, she would not be overtaken by it. I wanted to write someone who was totally unlike myself, never starstruck, never fangirl. She would not nerd out!

My protagonist was on the other side of the art form that felt to me so totalizing, so absorbing. As Helena came to me, it was often in a barrage of unexpected contradictions. I knew she needed to be a tyrant, and a powerhouse, but as she emerged she was also self-deprecating; she was an auteur but with a pulpy agenda, an anti-intellectual poseur and an arthouse snob whose successes are failures and vice versa — she was selfishly committed to her artistic vision, to the point of myopia, but that also meant she was emerging as someone difficult, incapable of collaboration, insensitive, exploitative, often manipulative. I knew she must be able to charm to seduce her conquests, but I felt she was also deeply disinterested in whether or not she was charming. There she was, hovering around and haunting the edges of my thinking, building up her own surface, her own way of seeing, a few too many opinions, and a whole heap of irreconcilable personality traits. I wrote her in full rant, but knew I also had to figure out how to write her inarticulation. She was driving me nuts, to be fair, and drawing out the process. Beyond this, the reality of writing a novel is that it takes more time than fourth and fifth hour STEM courses with revisions and book-bindings (the football fold) done in the commercial breaks during David Letterman.

I never expected to feel something for Helena beyond the challenge of having to make her seem real. But in fighting my way through her contradictions and her paradoxes, the answer was never true or false, never A or B, and I realized I was fixated on watching her sort through her vexed choices. By the time I had finished the book, I had begun to see her as a cheerleader for a certain kind of commitment to making art, someone resolved and stubbornly resistant to seeing her artistic process as the means to an end. This commitment to put her relationship to her art above almost every other relationship in her life doesn’t make for a seamless existence, nor will it make her relatable across the board for all readers, but she is a champion for being uncompromising about the importance of art, which as a writer, sometimes I feel is very difficult to sustain without a cheerleader.

As I continued to listen to her, I began to accept that Helena simply wouldn’t have an unimpeachable ethic, that her choices were not ones that would be easily reconcilable: she wasn’t solvable. But she certainly did choose her own adventures, and followed through. She was maddening, but compelling, attractive but dangerous as an object of affection, and suddenly I knew I had a serious crush. I began to imagine myself not as someone inhabiting her voice, but more like an actor in one of her projects, trying to teach myself how to see failure and see beyond failure as she did. I felt myself allowing her monologues to wash over me, allowing her Bernhardian pessimism to operate as comic relief, and as a release valve around my own anxiety about failure or success in my writing.

And so it came to pass, I was smitten with my protagonist. For the next installment in this romance, check your locker vent, or buy the book.