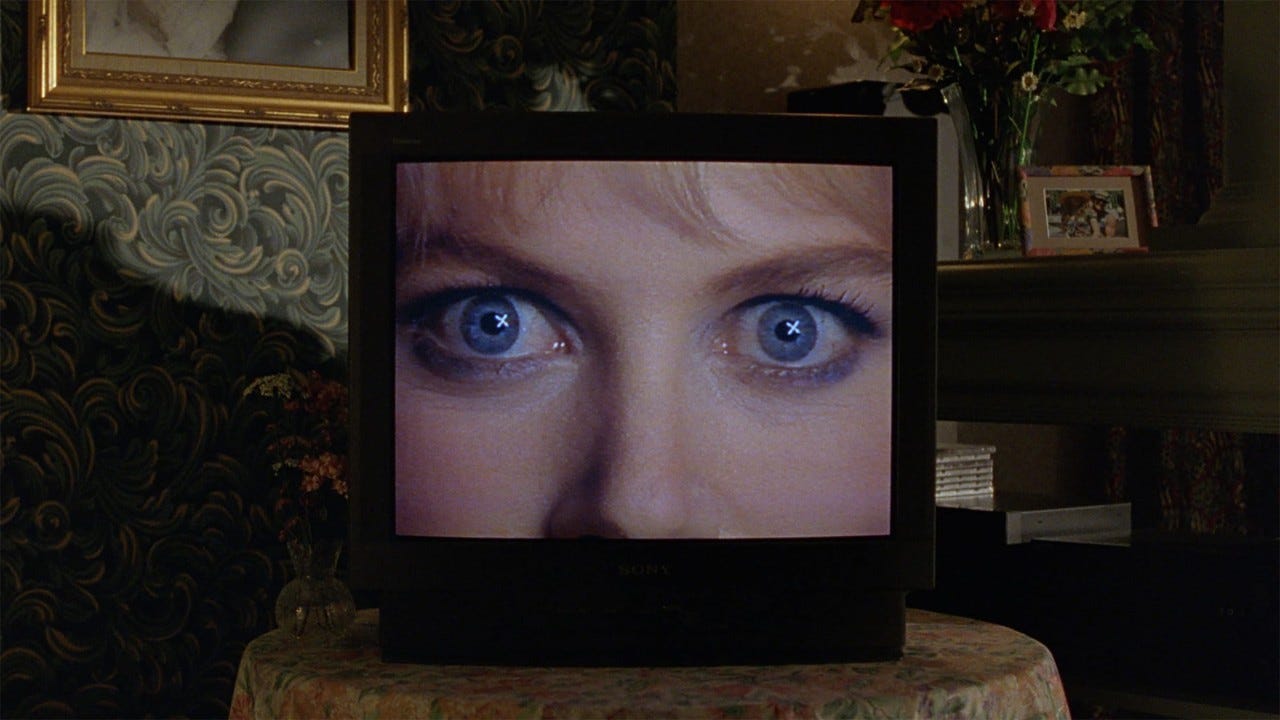

If you didn’t get it from her AMC ads, Nicole Kidman really, really loves film. She is a true cinema dirtbag and we salute her. We don’t cover much studio content here, but Kidman, more than any other superstar, has spent her entire career pushing herself into uncomfortable and challenging roles, whether it’s in Gus Van Sant’s first studio film, To Die For (1994), or Birth (2004), Jonathan Glazer’s still shattering second film.

To Die For is a thinly veiled adaptation of the real life case of Pamela Smart, who manipulated teenagers into killing her husband. The film is near-camp in its look and tone, but never loses its vicious bite or emotional punch. In Birth, an Upper Eastside executive is about to get remarried, but a 10-year-old boy shows up in her building and claims to be her late husband reincarnated. As she interrogates him, her façade of control breaks away, showing a woman still ruled by grief.

Also touched on in this commentary: Larry Clark’s Bully, the morality of adapting true crime, Salò and the power of artistic intention, Jim McBride’s 1967 version of reality TV, and who has the better mullet: Emily Schultz or Joaquin Phoenix?

BRIAN J DAVIS: Okay, so I’m going to retell a story from the commentary while this credit sequence plays. During a somewhat troubled post production—the studio wanted to dump To Die For straight-to-video—the writer, Buck Henry, decided all on his own that Illeana Douglas was the problem. He took a VHS copy of the rough cut of the film and on two VCRs he crappily pause-edited Douglas out of the movie, and proudly invited the stunned director and editor over to see it. They were doing everything to not laugh at him. That might be the most peak writer crazy I’ve ever heard about.

EMILY SCHULTZ: Illeana Douglas is one of the characters that I think is most memorable in this film!

BJD: Fake documentary: I have absolutely ripped off so much from To Die For over the years.

ES: The Blondes podcast wouldn’t exist without To Die For.

BJD: When you have something really plotty, fake documentary scenes allow you do a voluminous amount of storytelling. And then you don’t have to dramatize absolutely every last beat of a story, and bore your audience.

[A whip pan shot of a bar audience of girls in love with Matt Dillon’s character then ends on a dreamy-eyed boy.]

ES: I do think this is a very funny, short shot, the way that Van Sant works queerness into the edges of this very straight story.

BJD: And Illeana Douglas has a girlfriend that we glimpse in her hotel room.

ES: The one washing her hair and traveling everywhere with her? I didn’t catch that. Shit. Did I “roommate” her all these years?

BJD: Let’s talk about how Nicole Kidman is going far beyond an unlikable character here. She’s really digging deep into something that exists at the core of actors—wanting to be seen—and putting all its ugly excesses out there.

ES: The way she says things that she thinks are very deep and she’s coming off as so superficial. I remember having some aversion to this at the time, because it was a female character who’s so loathsome.

BJD: According to Kidman, it was the wigs that did a lot of the work! Once she had her ’90s newscaster bob wig on—

ES: I didn’t realize she was wearing a wig.

BJD: You know she’s a curly girl right? You don’t embrace her as a member of the curly community?

ES: I can't be acquainted with everyone in the community, Brian! And everyone had permed hair in the early ’90s.

BJD: There’s a lot of 1970s in this movie, despite it being 1994. A Buck Henry script, George Segal cameo, and it’s staking out a countercultural critique of TV shallowness.

ES: And now we’re in our hometown. This poverty on screen is strangely comforting.

BJD: I’m proud I was able to name the death metal track in a few seconds. “Ah, Nailbomb! Great Sepultura side project.” But I think it’s down to Van Sant, who brought Larry Clark realness to the teenager world in this film.

ES: Just how gross and psychotic they can be.

BJD: Here’s something I want to bring up. Sometimes true crime is not enough for good storytelling. Some things you can explain better when you add the fake stuff. In the Pamela Smart case she wasn’t trying to be famous—her motivation for murder was just sad, basic greed. But her trial was the first to be televised on cable TV. So that layer now enters this story, and in a way it makes it bearable. A good comparison of doing the exact opposite of this film—and proving me wrong— would be Bully. Speaking of Larry Clark.

ES: For going to absolute realism?

BJD: Yes. And in that film Larry Clark threw the written script out, and only used the book about the case to shoot from. Nothing was changed.

ES: And Bully is almost impossible to watch.

BJD: Actually, I just bought the new 4K from Umbrella, so we’ll see! But when I watched Bully the first time, I saw it at the theatre with a friend who was a conflict photographer. She covered civil wars, and she was shaken and moved by what Bully captured.

ES: Even reading the book, which I did again for Little Threats, the crime is so horrific and dumb.

BJD: Here’s my other thought during this viewing: How would they ruin To Die For now? Instead of letting her be this horrible, borderline personality monster, they would find some kind of compassion for Kidman’s character. Tease a little trauma to show how she was sent down this path.

ES: We’re in the golden age of “let’s reconsider these horrible people” and that doesn’t work for everything.

BJD: Not everyone is Magneto.

ES: A film needs to take a point of view. And this film does.

BJD: Okay, the Joaquin Phoenix school of dance begins in this movie! But you were also worried that you currently have his haircut.

ES: I totally have his hair because I have a mullet and all mullets are the same—there’s no elevated mullet! But really, on this viewing I related more to this film now, and one reason is because of Instagram and documentation and everybody filming themselves all the time, myself included.

BJD: There’s a great line from David Holzman's Diary, a fantastic 1967 film by Jim McBride about trying to put your life on film. A friend of the lead character is refusing to be filmed, and it’s totally a scripted moment. He declares, “When there’s a camera on me I stop making moral decisions. I start making technical ones.” And wow, I've been Lydia in that situation so many times.

ES: You have to go take the dog out for a walk while friends get it on and plan a murder?

BJD: Absolutely—I’m such a Lydia. I’m kind of torn about which is the performance of the film. Nicole Kidman is so committed, but Joaquin Phoenix has landed from a different planet. But there’s also the filmmaking, which is so expedited for such a dense script. The dusting of the television for prints while there’s an American flag signing off?

ES: The 1990s took risks!

BJD: Not with the ’90s, please. We weren’t the greatest generation, you know. Hope in our hearts, and a bong in our hands.

ES: And now it ends on the second best use of Donovan as a music cue in a film!

BJD: Living in New York as long as I have now, I do appreciate more that this happens to an Upper East Side family. Because those can be very serious and uptight people and that makes the situation at the heart of Birth even more hilarious. To me at least. They’re the closest you get to European-style bourgeois in America.

ES: Whereas if Anna was in our Brooklyn world, she would be talking about her reincarnated husband on IG, all the time.

BJD: This is what I’m afraid of every day when you go jogging in New York City.

ES: Oh, that I’ll have a heart attack under a bridge somewhere? I don’t jog when it's this snowy. Actually, this is quite a nice setup in terms of the first dialogue you get is that far in and it’s just one word: Okay. And here’s Nicole with short hair — might have been one of the reasons I really liked this movie in fact.

BJD: I’ll come back to Anne Heche again because I think is this is the Anne Heche performance as the former sister-in-law. I find her cruelty has so much depth.

ES: Is it cruel or was she trying to set Nicole Kidman free from her love?

BJD: Or you can see it as her punishment for being able to move on.

ES: Right, this is Kidman’s engagement party that she’s showing up at, after all.

BJD: About the controversy. This film has a better reputation post–Zone of Interest, but for years, because of “the scenes,” Birth was treated like Ken Russell’s The Devils by its studio. Birth existed, per se, but it was never available to stream until The Zone of Interest Oscar nomination. There was a lone DVD release in 2005, and there’ll probably never be a Blu-ray. That’s as buried as a Nicole Kidman film can get.

ES: America worries about the wrong things. This all comes out of a child’s capacity for imagination.

BJD: Look at the chaos it causes in the film. This is also about the delusional aspects of love. It makes us think what we’re imaging is real.

ES: When I was 10 I believed that could see the ghost of Abraham Lincoln everywhere. Like, why would Abraham Lincoln be hiding out in Canada?

BJD: I can think of one very important reason…

BJD: Jean-Claude Carrière, probably my favorite screenwriter for the work he did with Luis Buñuel, co-wrote this with Jonathan Glazer, who really did develop the script with him based on a one-line pitch. This film is such a fusion: the amour fou and delicate farce from Carrière, and Glazer fully moving into his Kubrick minimalism. It’s one of the best films ever made.

ES: Could you defend the scenes to someone who might disagree?

BJD: I mean intention is everything. And the intention in this film is to use the absurdity of the practicalities of reincarnation, while the moment between Anna and Sean in the bath only serves to emphasize their parent and child relationship. Love, like faith, can drive you into a ludicrous world view. On the opposite side of the spectrum there’s Pasolini’s Salò. It’s meant to be horrifying. It’s meant to hurt you. And it does. That’s the power of intention. One kind of film I do find…odd… are those beloved magical body or age swap comedies, where a 30-year-old woman is really a 13-year-old. Like, what’s the intention there?

ES: Birth plays its concept so straight-faced and serious. But it tells us the truth from the first scene on. We choose not to see it.

BJD: I remember after the big reveal watching this the first time, and I’m sure I actually slapped my forehead after watching this entire movie buying into “Maybe this is a metaphysical mystery?”

ES: I remember thinking, “What was that opening scene with Anne Heche and the second present all about?”

BJD: I read it as class anxiety—she didn’t get a nice enough present. How many times have I been invited into bougie-land, where I panicked that I didn’t bring a nice enough present or nice enough food.

ES: What this film does is keep secrets from the viewer, which I think is unusual. I think a lot of films pretend to keep secrets but they don’t actually.

BJD: Much like her husband Sean kept secrets!

ES: Let’s contrast this role with To Die For.

BJD: Here Kidman is disappearing into this character, because Anna has disappeared, she’s shrunk to this grief-space. It’s a performance that’s as quiet as To Die For is loud. And Danny Huston striving to be logical and supportive until he loses his shit in that amazing scene.

ES: What’s so interesting about this movie is that a young person is in control of things. He drives all of the action.

BJD: This goes back to that Buñuel connection via Carrière. Sean personifies amour fou: “No, I am this person I’m claiming to be.”

ES: He won’t give in and everyone starts to get worn down by this kid and his will!

BJD: The string quartet fight scene, where Danny Huston freaks out and attacks the kid with a piano. That is a definite Buñuel nod.

ES: Is it possible to lose to a ten-year-old? He’s lost because he couldn’t control himself.

BJD: And this is Kidman’s scene of the film, when she’s explaining the situation to her late husband’s brother and Anne Heche.

ES: We see Kidman is still fighting against the idea of reincarnation, but excited by it. We see her convert her belief system right there. This scene is almost like her announcing to family, “Hey I’ve met someone and by the way it’s probably your brother, reincarnated. We’re going to work it out.”

BJD: And Anne Heche is sitting there with a “This revenge turned out better than I expected” grin. Okay, on this viewing I’m noticing the complexity of Danny Huston’s character and what he has to deal with. It doesn’t matter if Sean is personified in this kid showing up or not, he is still facing a ghost…much like Gabriel in his father John Huston’s adaptation of James Joyce's The Dead. Thank you AP English class!

ES: Right, but unlike Michael Furey, Sean turns out to be a total asshole.

BJD: Who has two women in love with him…from beyond the grave!

ES: I did always feel like this was kind of a clumsy reveal—flashing back to Anne Heche burying the unopened letters she was going to give back to Nicole Kidman. Somebody wouldn’t do this — and yet it makes the story happen; it makes it move.

BJD: To me it’s not a plot point so much as competing visions of love. Anne Heche’s version involves deceit and cruelty and all of it—love has all those dimensions, whereas Nicole Kidman’s conception of love is actually quite innocent. She’s primed to believe. This again goes back to true bravery in choosing this role. She’s playing someone who has deluded herself into an embarrassing conclusion. She realizes she chose a delusion over the truth.

ES: Sean has fallen out of the dream but what’s interesting is she actually she speaks to him a child like a child throughout the movie, especially at the ending. She’s scolding him, as in a motherly relationship. Is that an acting choice or is that in the script?

BJD: I’m going say it’s an acting choice and a choice to keep things uncomfortable, but not jarring.

ES: “I’m not responsible for my reaction.” This girl is very 2024 in her non-apology to her fiancé.

BJD: And the wedding and Kidman running into the sea in her wedding dress, weeping. One of my favorite endings of a movie ever. The scene where she made up with Danny Huston wasn’t quite the real ending. This is the real ending, where the truth hits her.

ES: I think actually what’s interesting with that last shot is how Danny Huston does come for her to comfort her, and they walk away together, like a couple in an actual relationship.

BJD: Maybe it’s a hopeful breakdown? Now she can live.

ES: Okay, you can force Marjorie Taylor Greene to watch one of these movies. Which one?

BJD: Definitely Birth, because it would upset her so much. To Die For, she’d identify with the character too much. She’d feel seen!