ATROCITY EXHIBITIONISM

A new history of underground music has me thinking we've always lived inside an industrial music video

Art predicts the future by accident.

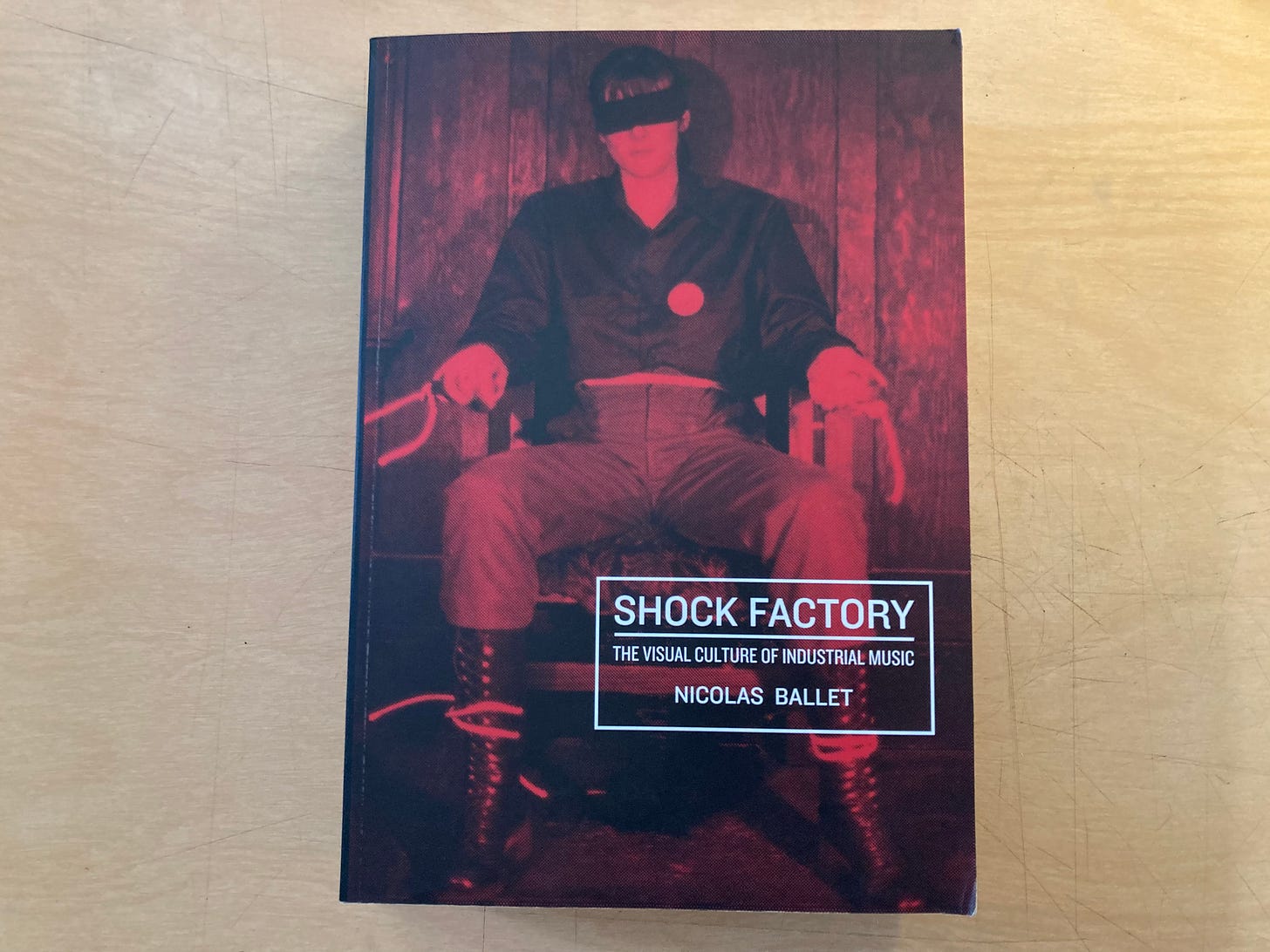

That was the thought I had on first flipping through Nicolas Ballet’s overwhelming and exhilarating tome, Shock Factory: The Visual Culture of Industrial Music. And industrial music—especially its first practitioners Throbbing Gristle, SPK, Cabaret Voltaire, Coil, and Test Dept—was well placed for that kind of prophecy. Starting in the UK and spanning the late 1970s and throughout the ’80s, industrial music connected the frayed ends of the hippy underground with the rise of the 24-hour news day, corporate media consolidation, the birth of the religious right, and the waning of the Eastern Bloc. Ideology was collaborating with technology in a way we had not experienced yet and the industrial bands were there to report back with homemade synthesizers, scavenged metal, and hand-cut tape loops. Juvenile-minded punk may have been all about its fragile present, but the industrial artists were happy to raid old avant-gardes and imagined futures for their visual palette of—allow me one more list—propaganda, extreme criminal deviancy, war, occult ritual, body politics, and information technology.

As Ballet argues in his introduction, taken as a whole, industrial music is its own alternative postmodernism.

By focusing exclusively on the visual trail left by the industrial scene, Ballet avoids reducing the scene’s efforts to some wierdo subset of pop music history and instead foregrounds the ideas. That’s appropriate, because for the most part these were not garage musician hopefuls. They were performance artists looking to undermine the idea of entertainment itself. Ballet’s 600-page cataloging is meticulous, insightful and at times horrifying. This is a genre that can still shock decades later, maybe because the framework among disparate artists is surprisingly consistent. Obsessed by the machines that manufacture everyday life, they believed our chromed and molded luxuries were made at the same factory as our blood- and dirt-covered horrors.

And therein lies the oft missed meaning of industrial culture: If you can learn how the totality is made—through its thought-killing cliches to use the phrase from psychologist Robert Jay Lifton—you can also take it apart. You can “short circuit the control process” as Throbbing Gristle’s Genesis Breyer P-Orridge tells Ballet.

For a genre built on discomfort, Ballet does not shy away from 2025 questions. Letting voices from the scene speak openly, Shock Factory addresses the aesthetic misogyny of many of the releases, along with personal failings. (The late P-Orridge did run a literal cult for several years, among their other accomplishments.) There’s also the problem of how this “laboratory of ambiguity” played with fascist imagery, for both subversive and fetishistic reasons. (Keep in mind this goes back to bands as prosaic as the Rolling Stones or fashion houses like YSL.) For Ballet, the use of these aesthetics will ultimately escape the control of the artist, no matter how ironic they intend to be. He writes, “The power of the visuals used has the capacity to blur the original purpose of dissent.”

That said, Ballet resists easy judgements. What is “good” industrial or “failed” industrial is up to the reader and for readers like myself that can be a personal question.

At the beginning of my career there were zines and collage mail art. Like many of the artists in Shock Factory I found my source material at thrift stores or in dollar bins at places like John K King Books: medical textbooks on skin diseases, monographs about Minamata victims, 1960s leftist paperbacks. There was also my tape. Inspired from reading about, yet being too young to have experienced SPK or Cabaret Voltaire live shows, the tape was cut with a Radio Shack video editor and collected scenes from: Holy Mountain; political assassinations; NFB films from the library; primal scream therapy; video nasties; Jonestown; and Kaiju fights. It was for any band gullible enough to be believe I was a renowned video artist at 19. It was a bit rich that I labelled it “Deprogramming Tape” but at least for me that title was correct. Even if it crossed fully over into self-parody, I was still learning montage in the Eisenstein-sense: how an image changed when it was pushed against another image; how emotions could be sampled and altered, like anything else.

As an adult I know there is real pain behind some of these source images. My favorite punk album cover design growing up was Discharge’s Hear Nothing See Nothing Say Nothing, which juxtaposes, among other images, sunbathing shots with napalm burns. Why was I drawn to that? Susan Sontag wrestled with questions like this in her final book, Regarding the Pain of Others. (And which is quoted throughout Shock Factory). Sontag was, at the end of her life, pessimistic about the effect of atrocity imagery. That it might do little to sway anyone’s opinion because our well-intended compassion can be short-lived while in front of horrible images, perhaps even more so the more horrific they are. Yet when I think about the fold out Crass1 poster above my teenage bed of a war destroyed, burned-hand with the slogan “Your Country Needs You,” and why I hung it there, my motivation of don’t become working class cannon fodder seems pretty solid in retrospect. 2

Ironically, as the extreme signifiers of the industrial scene were incorporated into the mainstream and hybrids like industrial rock and nu metal, many of the pioneers featured in this book had already left the dystopia behind and eased into dance music and the utopia of the 1990s and beyond. And that conversion is completely understandable. Emotionally, intellectually, and even physically, you can’t stay in the Black Lodge forever. As well, the technology itself was changing. Samplers, sequencers, layout, and video had all gone digital and this democratization of media tools along with the mass dissemination of information and culture through the internet would change everything for the better.

That was the plan, anyway.

Instead, social media feeds in 2025 can seem like Ludovico treatments of disparate, clashing videos of local crime, skin care routines, self-appointed gurus, uprisings, AI, cult-like memes, and citizen reports on genocide. That is to say, it’s a lot like an industrial clip tape made by an 18-year-old looking for the meaning to life by sorting through its most brutal, finger-cutting pieces.

There’s now significant social pressure to not engage with social media, with the idea that using social media co-signs the legitimacy of dark forces. I’m no electoral wonk, but I did notice Democratic candidates spending the last four years comically terrified of podcasts—almost as much as the Vatican was once terrified of the Gutenberg press. Also, legacy media believed Substack was the coming of the Antichrist. Perhaps in trying to maintain past hierarchies that don’t exist anymore the liberal center is at continual risk of ceding every new platform to the right.

At one time in the late 1980s Skinny Puppy3 was putting out so many 12-inch singles that sampled the news of only a couple months previous that their songs operated as relatively real time remixes of history. That this is how I learned the truth about Middle East conflicts or America’s AIDS policies is no different than someone today learning socialism 101 through YouTube essays.

Even Cabaret Voltaire had one final act of subversion, via a pressing plant error, when a Taylor Swift fan took to TikTok in 2023. She described how the Swift album she bought had music that turned out to be a mix of Cabaret Voltaire’s track “Yashar.” According to the Guardian, “Despite initially finding it ‘so creepy’ Hunter has come around to the Cabaret Voltaire track. ‘When the beat kicks in I was like: this is a vibe.’”

The images we’re watching right now are as threatening as anything from the twentieth century. It’s easy to feel, in the words of Einstürzende Neubauten, “Power is a non-stop tape and my ears are wounds.” But we should resist the urge to look away in retreat from technology. As Ballet argues, “[The] industrial bands’ fascination with the worst that humanity has to offer comes from a profoundly humanist worldview.”

Even more than looking, you should use whatever tools you can or, in the anti-tradition of industrial culture, abuse them.

One hill I will die on: Crass was an industrial band disguised as a punk band. I know this because no one, to this day, sounds like Crass whereas a million bands sound like Discharge.

Not to dunk too much on a writer I otherwise like, but Sontag is wrong at the end of Regarding the Pain the Others. Given the Chelsea penthouse perch of Sontag’s worldview, my need for anti-propaganda was something she could never conceive of, no matter how sharp her writing was on the elusive emotions of photographs.

Skinny Puppy rates a single mention in Shock Factory because they are still the industrial band that can’t get no respect. That is for one reason only: Canadian. I suggest you revisit their one two punch of masterpieces, VIVIsectVI and Rabies. One a dense, sculpted soundscape, the other a collection of goth night bangers.

This is great--thank you!